Fixing Our Broken Housing Market White Paper

Introduction Our Housing Market is Broken

The housing market in this country is broken, and the cause is very simple: for too long, we haven’t built enough homes.

Since the 1970s, there have been on average 160,000 new homes each year in England.[1] The consensus is that we need from 225,000 to 275,000 or more homes per year to keep up with population growth and start to tackle years of under-supply.[2]

This isn’t because there’s no space, or because the country is “full”. Only around 11 per cent of land in England has been built on.[3]

The problem is threefold: not enough local authorities planning for the homes they need; house building that is simply too slow; and a construction industry that is too reliant on a small number of big players.

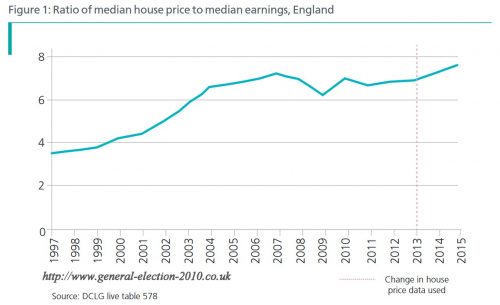

The laws of supply and demand mean the result is simple. Since 1998, the ratio of average house prices to average earnings has more than doubled.4 And that means the most basic of human needs – a safe, secure home to call your own – isn’t just a distant dream for millions of people. It’s a dream that’s moving further and further away.

In 21st century Britain it’s no longer unusual for houses to “earn” more than the people living in them. In 2015, the average home in the South East of England increased in value by £29,000,5 while the average annual pay in the region was just £24,542.6 The average London home made its owner more than £22 an hour during the working week in 20157 – considerably more than the average Londoner’s hourly rate. That’s good news if you own a property in the capital, but it’s a big barrier to entry if you don’t.

Figure 1: Ratio of Median House Price to Median Earnings, England

The Council of Mortgage Lenders predicts that by 2020 only a quarter of 30-year-olds will own their own home. In contrast, more than half the generation currently approaching retirement were homeowners by their 30th birthday.[8] This is not because young people are not trying hard enough, it’s because it is much harder for them to get a foot on the property ladder than their parents and grandparents.

As recently as the 1990s, a first-time buyer couple on a low-to-middle income saving five per cent of their wages each month would have enough for an average-sized deposit after just three years. Today it would take them 24 years.[9] It’s no surprise that home ownership among 25- to 34-year-olds has fallen from 59 per cent just over a decade ago to just 37 per cent today[10].

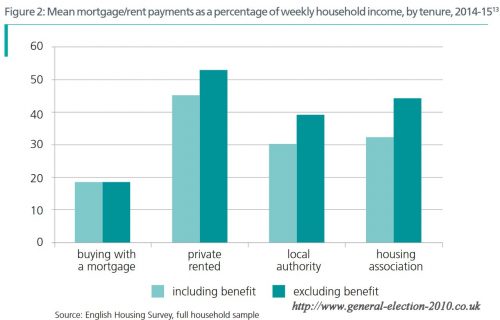

Without help from the “Bank of Mum and Dad”, many young people will struggle to get on the housing ladder. As demand for homes outstrips supply, they’re faced with ever-increasing rents – the average couple in the private rented sector now send roughly half their salary to their landlord each month[11] making it nigh on impossible to save for a deposit.

In areas where the housing shortage is most acute, high demand and low supply is creating opportunities for exploitation and abuse: unreasonable letting agents’ fees, unfair terms in leases, landlords letting out dangerous, overcrowded properties. In short, it’s becoming harder to rent a safe, secure property. And more and more people can’t find a place to rent at all: the loss of a private sector tenancy is now the most common cause of homelessness.[12]

Figure 2: Mean Mortgage/Rent Payments as a Percentage of Weekly Household Income, by Tenure, 2014-15[13]

Source: English Housing Survey, full household sample

Notes:

1. based on gross income from HRP and partner only

2. Housing benefit or Local Housing Allowance (LHA) or Universal Credit received by the householder to help pay for all or part of their rent. This only applies to households that rent their home.

Britain’s broken housing market hurts all of us. Sky-high property prices stop people moving to where the jobs are. That’s bad news for people who can’t find work, and bad news for successful companies that can’t attract the skilled workforce they need to grow, which is bad news for the whole economy.

Low levels of house building means less work for everyone involved in the construction industry – architects, builders, decorators and manufacturers of everything from bricks to kitchen sinks. If people must spend more and more to keep a roof over their head they’ll inevitably cut back elsewhere – meaning less money gets spent in the wider economy.

High rents are bad news for all taxpayers including those who own their own home. If rents are too high, then private renters struggle to pay – and the taxpayer has to foot the bill with more Housing Benefit. That’s money that could be spent on schools, hospitals and other frontline services.

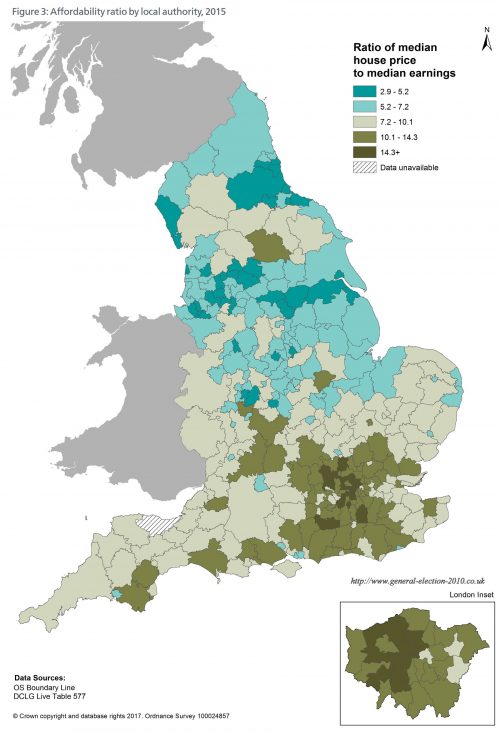

Nor is this just a London problem. While the situation is particularly acute in and around the capital, it is also getting worse right across the country. Since 1997 house prices relative to earnings have more than doubled in Lancaster, Manchester and Boston.[14]

This is a national issue that touches every one of us. Everyone involved in politics and the housing industry has a moral duty to tackle it head on.

Figure 3: Affordability Ratio by Local Authority, 2015

The challenges we face

Building more homes will depend on our dealing with three major problems.

First, over 40 per cent of local planning authorities do not have a plan that meets the projected growth in households in their area.[15] There are many reasons for this, but one of the most significant is the way local decision-makers respond to public attitudes about new housing.

Quite reasonably, people often have concerns about the impact new housing will have on their community. That is why it is so important that people have a say over where new homes go and what they look like through the planning process. People are more likely to support new mansion blocks or mews houses on a derelict strip of land than a new estate in countryside. Many councils work tirelessly to engage their communities on the number, design and mix of new housing in their area. But some duck difficult decisions and don’t plan for the homes their area needs.

Without an adequate plan, homes can end up being built on a speculative basis – with no co-ordination and limited buy-in from local people. The uncertainty this creates about when and where new homes will be built is both unpopular and affects the entire house building process – slowing it right down.

And that’s the second big problem: the pace of development is too slow. This Government’s reforms have led to a large increase in the number of homes being given planning permission. But there is a large gap between permissions granted and new homes built. More than a third of new homes that were granted planning permission between 2010/11 and 2015/16 have yet to be built.[16]

There can be various reasons for these delays. If there isn’t a robust local plan, permission may be contested and it stops infrastructure and utility companies planning ahead. Changes to market conditions and onerous planning conditions can also be factors.

But there is also concern that it may be in the interest of speculators and developers to snap up land for housing and then sit back for a while as prices continue to rise.

Figure 4: Annual Completions Versus Permissions

Source: Glenigan planning permissions data; DCLG Live Table 120

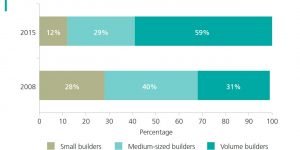

Finally, the very structure of the housing market makes it harder to increase supply. Housing associations have been doing well – they’re behind around a third of all new housing completed over the past five years[17] – but the commercial developers still dominate the market.

And within that sector, a handful of very big companies are responsible for most new building. Britain’s 10 largest housebuilding firms build around 60 per cent of our new private homes.[18]

Homes are typically bought with debt, so a slight change in interest rates can have a big impact on people’s ability to afford a new home. This government has kept spending under control, avoiding the dangers of higher mortgage rates.

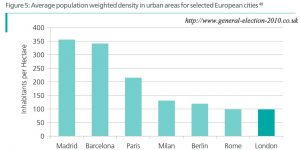

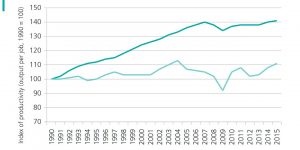

But building at scale still exposes commercial developers to significant financial risk. So, there is little incentive to invest in innovative methods of construction which could deliver many more homes. Over the past 25 years, productivity across the whole economy has grown by 41 per cent as new technology and new ways of working make business and industry more efficient and effective. In construction, it has grown by just 11 per cent – almost four times slower.[19]

What we’re going to do about it

The cause of our housing shortage is simple enough– not enough homes are being built. Fixing it is more complex. This is a problem that has built up over many decades, and solving it requires a radical re-think of our whole approach to home building.

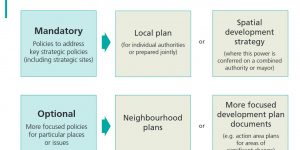

First, we need to plan for the right homes in the right places. This is critical to the success of our modern industrial strategy. Growing businesses need a skilled workforce living nearby, and employees should be able to move easily to where jobs are without being forced into long commutes.

But at the moment, some local authorities can duck potentially difficult decisions, because they are free to come up with their own methodology for calculating ‘objectively assessed need’. So, we are going to consult on a new standard methodology for calculating ‘objectively assessed need’, and encourage councils to plan on this basis.

We will insist that every area has an up-to-date plan. And we will increase transparency around land ownership, so it is clear where land is available for housing and where individuals or organisations are buying land suitable for housing but not building on it. This will put communities back in charge of getting the attractive homes they want and need – for young professionals, older people, growing families, people on low incomes, people with disabilities and more.

It will reduce speculative development, and support our villages, towns and cities to develop in a way that preserves the unique character of their communities, and protects precious countryside.

Second, we need to build homes faster. We will invest in making the planning system more open and accessible, and tackle unnecessary delays.

Development is about far more than just building homes. Communities need roads, rail links, schools, shops, GP surgeries, parks, playgrounds and a sustainable natural environment. Without the right infrastructure, no new community will thrive – and no existing community will welcome new housing if it places further strain on already stretched local resources.

We’re giving councils and developers the tools they need to build more swiftly, and we expect them to use them. Local authorities should not put up with applicants who secure planning permission but don’t use it. And they will have nowhere to hide from this government if they fail to plan and deliver the homes this country needs.

Third, we will diversify the housing market, opening it up to smaller builders and those who embrace innovative and efficient methods. We set out how we will support housing associations to build more, explore options to encourage local authorities to build again, encourage institutional investment in the private rented sector and promote more modular and factory built homes. We will also make it easier for people who want to build their own homes.

These measures will make a lasting, positive impact on housing supply, but they will inevitably take time to have an effect. So, finally, we will help people now – from investing in affordable housing to banning unfair letting agent fees to preventing homelessness.

A problem that won’t solve itself

The housing shortage isn’t a looming crisis, a distant threat that will become a problem if we fail to act. We’re already living in it. Our population could stop growing and net migration could fall to zero, but people would still be living in overcrowded, unaffordable accommodation. Infrastructure would still be overstretched. This problem is not going to go away by itself.

If we fail to build more homes, it will get ever harder for ordinary working people to afford a roof over their head, and the damage to the wider economy will get worse.

This isn’t a new problem. Its roots stretch back decades, with house building well below what was needed under successive governments. And it’s not a problem we can afford to ignore any longer.

Tackling the housing shortage won’t be easy. It will inevitably require some tough decisions. But the alternative is a divided nation, with an unbridgeable and ever-widening gap between the property haves and have-nots. A country where only those with wealthy parents can get a foot on the property ladder and where elderly people are forced to keep working in order to pay off their mortgage.

We want this to be a country that works for everyone, where people who work hard can afford a place of their own. This White Paper is an important step in delivering just that.

1 DCLG Live Table 104.

2 For example: Barker (2004), “Review of Housing Supply – Delivering Stability: Securing our Future Housing Needs” Final Report; House of Lords Select Committee on Economic Affairs (2016), “Building more homes”, July 2016; KPMG and Shelter (2015) “Building the Homes We Need”.

3 DCLG Local authority green belt statistics for England: 2015 to 2016, page 2, available at https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/local-authority-green-belt-statistics-for-england-2015-to-2016

4 DCLG Live Table 577.

5 ONS House Price Statistics for Small Areas, Table 1a.

6 ONS Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings 2016, table 3.7a, median annual gross pay, all employee jobs.

7 ONS House Price Statistics for Small Areas, Table 1a.

8 Council of Mortgage Lenders (2015) The challenge facing first-time buyers.

9 Resolution Foundation (2015) – Dealing with the housing aspiration gap.

10 English Housing Survey 2014/15.

11 English Housing Survey 2014/15.

12 DCLG Live Table 774.

13 English Housing Survey 2014/15; statistic refers to the income of the household reference person (the person in whose name the dwelling is owned or rented) plus that of a partner (including income from benefits).

14 DCLG Live table 577.

15 DCLG data collected on local plans; DCLG Live tables on household projections, 2016 to 2026.

16 Glenigan planning permissions data; DCLG Live Table 120 (new build completions).

17 DCLG Live tables on house building; DCLG Live tables on affordable housing supply.

18 NHBC Market Intelligence report 2015; DCLG Live Table 209.

19 ONS Labour Productivity statistics.

Previous : Foreword from the Secretary of State

Next : Chapter 1: Planning For The Right Homes In The Right Places

Here is an idea: how about the bankers, speculators and BTLers are forced to retreat from the housing market, pushing prices down and, alas, making housing more affordable.

The notion that demand outstrips supply is a myth promoted by the establishment and reiterated in the white paper to justify high prices.

The reality is that there are thousands of flats ready to move in – even in London.

The problem is that they are too expensive.

So there is no supply problem.

The problem is that the supply is not at an affordable price.

How To Make Housing More Affordable