Fixing Our Broken Housing Market White Paper

Chapter 1: Planning For The Right Homes In The Right Places

Summary

If we are to build the homes this country needs, we need to make sure that enough land is released in the right places, that the best possible use is made of that land, and that local communities have control over where development goes and what it looks like.

This chapter sets out our proposals to:

make sure every part of the country has an up-to-date, sufficiently ambitious plan so that local communities decide where development should go;

simplify plan-making and make it more transparent, so it’s easier for communities to produce plans and easier for developers to follow them;

ensure that plans start from an honest assessment of the need for new homes, and that local authorities work with their neighbours, so that difficult decisions are not ducked;

clarify what land is available for new housing, through greater transparency over who owns land and the options held on it;

make more land available for homes in the right places, by maximising the contribution from brownfield and surplus public land, regenerating estates, releasing more small and medium sized sites, allowing rural communities to grow and making it easier to build new settlements;

maintain existing strong protections for the Green Belt, and clarify that Green Belt boundaries should be amended only in exceptional circumstances when local authorities can demonstrate that they have fully examined all other reasonable options for meeting their identified housing requirements;

give communities a stronger voice in the design of new housing to drive up the quality and character of new development, building on the success of neighbourhood planning; and

make better use of land for housing by encouraging higher densities where appropriate, such as in urban locations where there is high housing demand; and by reviewing space standards.

More details of these proposals, and questions for consultation, can be found in the annex.

The case for change

1.1 Up-to-date plans are essential because they provide clarity to communities and developers about where homes should be built and where not, so that development is planned rather than the result of speculative applications. At present too few places have an up-to-date plan: at the end of January 2017, 34 local planning authorities had not published a local plan for consultation, despite having had over twelve years to do so; and only a third of authorities had adopted a plan since the National Planning Policy Framework was published in March 2012.[20] Even where plans are in place they may not be fulfilling their objective to recognise and plan for the homes that are needed.

1.2 Plan-making remains slow, expensive and bureaucratic, with arguments about the number of homes to be planned for often being a particular cause of delay – something not helped by the lack of a standard methodology for assessing housing requirements. We want to ensure that every area has an effective, up-to-date, plan – by making it easier for plans to be produced and understood, and simpler to identify the homes that are required. Effectiveness means plans meeting as much of that housing requirement as possible, in ways that make good use of land and result in well-designed and attractive places to live.

1.3 In spite of the progress being made to bring more brownfield land back into use, plans don’t always encourage a sufficiently wide range of sites to come forward to meet local housing requirements. Often, there is also scope to involve the community earlier in the design of schemes, and to do more with the land which is identified, so homes can be accommodated efficiently. We remain committed to our manifesto promise to protect the Green Belt.

1.4 In response, this chapter sets out our proposals to reform plan-making, identify sufficient land in the right locations and make the most of development opportunities; with more community involvement to secure the best outcomes for both people and places.

1.5 A number of the proposals build on consultations and reviews conducted over the last year: the report of the Local Plans Expert Group; consultations on changes to the National Planning Policy Framework,[21] technical changes to planning and ‘building up’ in London; and the Rural Planning Review call for evidence.[22] The Government has taken account of responses to these consultations in deciding the way forward. A summary of the responses to each consultation is being published alongside this White Paper.

Getting plans in place

Making sure every community has an up-to-date, sufficiently ambitious plan

1.6 We are legislating through the Neighbourhood Planning Bill to put beyond doubt the requirement for all areas to be covered by a plan. Authorities that fail to ensure an up-to-date plan is in place are failing their communities, by not recognising the homes and other facilities that local people need, and relying on ad hoc, speculative development that may not make the most of their area’s potential.

1.7 Our proposals in this White Paper will make plans easier to produce, and we will provide authorities with the support they need. But, as we have indicated previously,[23] we will, when necessary, intervene to ensure that plans are put in place, so that communities in the areas affected are not disadvantaged by unplanned growth. New powers proposed in the Neighbourhood Planning Bill will strengthen our ability to do so.

1.8 We also want to strengthen expectations about keeping plans up-to-date. Plans should be reviewed regularly, and are likely to require updating in whole or in part at least every five years. The Neighbourhood Planning Bill proposes to allow the Secretary of State to require local planning authorities to review local plans and other local development documents at prescribed intervals. We will set out in regulations a requirement for these documents to be reviewed at least once every five years. An authority will need to update their plan if their existing housing target can no longer be justified against their objectively assessed housing requirement, unless they have agreed a departure from the standard methodology with the Planning Inspectorate.

1.9 Where an authority has demonstrated that it is unable to meet all of its housing requirement, it must be able to work constructively with neighbouring authorities on how best to address the remainder. The duty to co-operate already places a legal requirement on local planning authorities to collaborate where cross-boundary issues arise during plan-making. However in some parts of the country this has not been successful. To address this we will consult on changes to the National Planning Policy Framework, so that authorities are expected to prepare a Statement of Common Ground, setting out how they will work together to meet housing requirements and other issues that cut across authority boundaries.

Making plans easier to produce

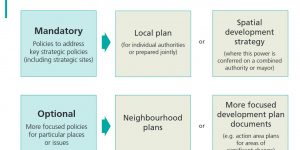

1.10 Plan-making remains expensive and bureaucratic, and can appear inaccessible to local communities. Building on measures in the Neighbourhood Planning Bill we propose to:

ensure that every authority is covered by a plan, but remove the expectation that they should be covered by a single local plan.

Instead, we will set out the strategic priorities that each area should plan for, with flexibility over how they may do so. The changes will also make clear that documents should not duplicate one another unless clearly justified; amend the tests for assessing whether a plan is ‘sound’;

and make the evidence needed to support plans more proportionate;

enable spatial development strategies, produced by new combined authorities or elected Mayors, to allocate strategic sites;[24] and

improve the use of digital tools to make plans and planning data more accessible, and review the consultation and examination procedures for all types of plan to ensure they are proportionate.

1.11 Further details of our proposals are set out in the annex.

Assessing housing requirements

1.12 The current approach to identifying housing requirements is particularly complex and lacks transparency. The National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) sets out clear criteria but is silent on how this should be done. The lack of a standard methodology for doing this makes the process opaque for local people and may mean that the number of homes needed is not fully recognised. It has also led to lengthy debate during local plan examinations about the validity of the particular methodology used, causing unnecessary delay and wasting taxpayers’ money. The Government believes that a more standardised approach would provide a more transparent and more consistent basis for plan production, one which is more realistic about the current and future housing pressures in each place and is consistent with our modern Industrial Strategy. This would include the importance of taking account of the needs of different groups, for example older people.

1.13 The Government will, therefore, consult on options for introducing a standardised approach to assessing housing requirements. We will publish this consultation at the earliest opportunity this year, with the outcome reflected in changes to the National Planning Policy Framework.

1.14 We want councils to use the new standardised approach as they produce their plans and will incentivise them to do so. We expect councils that decide not to use the new approach to explain why not and to justify to the Planning Inspectorate the methodology they have adopted in their area. We will consult on what constitutes a reasonable justification for deviating from the standard methodology, and make this explicit in the National Planning Policy Framework.

1.15 To incentivise authorities to get plans in place, in the absence of an up-to-date local or strategic plan we propose that by April 2018 the new methodology for calculating objectively assessed requirement would apply as the baseline for assessing five year housing land supply and housing delivery. In specific circumstances where authorities are collaborating on ambitious proposals for new homes, the Secretary of State would be able to give additional time before this new baseline applies. We will consult on these proposals.

1.16 Whatever the methodology for assessing overall housing requirements, we know that more people are living for longer. We propose to strengthen national policy so that local planning authorities are expected to have clear policies for addressing the housing requirements of groups with particular needs, such as older and disabled people.

Making land ownership and interests more transparent

1.17 It can be difficult to establish the identity of all persons with an interest in land. The Government would like to make data about land ownership, control and interests more readily available to all. This will help identify land that may be suitable for housing, allow communities to play a more active role in developing plans, support digital plan-making, help new entrants to the market and offer wider benefits. We are therefore launching an ambitious programme to improve the availability of land and property data.

1.18 HM Land Registry is committed to becoming the world’s leading land registry for speed, simplicity and an open approach to data and will aim to achieve comprehensive land registration by 2030. This will include all publicly-held land in the areas of greatest housing need being registered by 2020, with the rest to follow by 2025. It will aid better data sharing across government for the purposes of supporting development, ensuring financial stability, tax collection, law enforcement and the protection of national security.

1.19 Alongside the improved registration of land, the Government proposes to improve the availability of data about wider interests in land. There are numerous ways of exercising control over land, short of ownership, such as through an option to purchase land or as a beneficiary of a restrictive covenant. There is a risk that because these agreements are not recorded in a way that is transparent to the public local communities are unable to know who stands to benefit fully from a planning permission. They could also inhibit competition because SMEs and other new entrants find it harder to acquire land. There is the additional risk that this land may sit in a ‘land bank’ once an option has been acquired without the prospect of development.

1.20 The Government will consult on improving the transparency of contractual arrangements used to control land. Following consultation, any necessary legislation will be introduced at the earliest opportunity. We will also consult on how the land register can better reflect wider interests in land with the intention of providing a ‘clear line of sight’ across a piece of land setting out who owns, controls or has an interest in it.

1.21 The Government also proposes to improve the availability of data about wider interests in land by:

releasing, free of charge, its commercial and corporate ownership data set, and the overseas ownership data set, and publishing a draft Bill to implement the Law Commission’s proposals for the reform of restrictive covenants and other interests.

Making enough land available in the right places

1.22 Local planning authorities have a responsibility to do all they can to meet their housing requirements, even though not every area may be able to do so in full. To strengthen expectations, the Government is proposing to amend the National Planning Policy Framework so that when preparing plans:

authorities should have a clear strategy to maximise the use of suitable land in their area, so it is clear how much development can be accommodated; and

their identified housing requirement should be accommodated unless there are policies elsewhere in the National Planning Policy Framework that provide strong reasons for restricting development, or the adverse impacts of meeting this requirement would significantly and demonstrably outweigh the benefits.

1.23 What this means in practice will depend on the housing requirements and opportunities in each area, but we are proposing a number of changes to underline particular priorities that should be pursued.

Bringing brownfield land back into use

1.24 We must make as much use as possible of previously-developed (‘brownfield’) land for homes

– so that this resource is put to productive use, to support the regeneration of our cities, towns and villages, to support economic growth and to limit the pressure on the countryside. The Government is already pursuing a number of reforms to make this happen, as set out in the annex.

1.25 Going further, the presumption should be that brownfield land is suitable for housing unless there are clear and specific reasons to the contrary (such as high flood risk). To make this clear, we will amend the National Planning Policy Framework to indicate that great weight should be attached to the value of using suitable brownfield land within settlements for homes, following the broad support for this proposal in our consultation in December 2015.[25]

More homes on public sector land

1.26 We have a particular responsibility to make the most of surplus land which is already in public ownership. The Government has an ambition to release surplus public land with capacity for 160,000 homes during this Parliament. We are operating our Accelerated Construction programme on some of this land. Local authorities are working on parallel proposals to use surplus public land for a further 160,000 homes over the Parliament. We are providing further support for local authorities by launching a new £45m Land Release Fund and have already had a large number of expressions of interest for participation in the Accelerated Construction programme outlined in Chapter 3.

1.27 In addition, we propose to ensure all authorities can dispose of land with the benefit of planning permission which they have granted to themselves. We will also consult on extending their flexibility to dispose of land at less than best consideration and welcome views on what additional powers or capacity they need to play a more active role in assembling land for development (including whether additional powers are needed to prevent ‘ransom strips’ delaying or preventing development, especially in brownfield regeneration). For example, in many countries local authorities regularly work with local landowners to assemble land for housing (see case study from Bonn below).

1.28 In support of the Government’s national strategy on estate regeneration,[26] we also propose to amend national policy to encourage local planning authorities to consider the social and economic benefits of estate regeneration, and use their planning powers to help deliver this to a high standard.

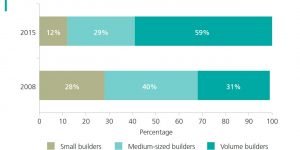

Supporting small and medium sized sites, and thriving rural communities

1.29 Policies in plans should allow a good mix of sites to come forward for development, so that there is choice for consumers, places can grow in ways that are sustainable, and there are opportunities for a diverse construction sector. Small sites create particular opportunities for custom builders and smaller developers. They can also help to meet rural housing needs in ways that are sensitive to their setting while allowing villages to thrive.

1.30 Reflecting proposals set out in the Government’s previous consultation on changes to the National Planning Policy Framework,[27] we will:

amend national policy to expect local planning authorities to have policies that support the development of small ‘windfall’ sites (those not allocated in plans, but which come forward on an ad hoc basis); and

indicate that great weight should be given to using small undeveloped sites within settlements for homes, where they are suitable for residential development.[28]

1.31 These changes apply to all types of area. Together with the additional weight that national policy will place on the benefits of developing brownfield land, they will ensure there is a clear presumption that residential development opportunities on small sites should be treated positively. We will ensure councils can continue to protect valued areas of open space and the character of residential neighbourhoods, and stop unwanted garden grabbing.

1.32 There are opportunities to go further to support a good mix of sites, meet rural housing needs and increase the supply of land available to small and medium sized house builders.

1.33 We are proposing a number of additional changes to the National Planning Policy Framework to:

give much stronger support for sites that provide affordable homes for local people;[29]

highlight the opportunities that neighbourhood plans present for identifying and allocating sites that are suitable for housing, drawing on the knowledge of local communities;

Images © roettgen-online.com

Bonn city council has made extensive use of land pooling and typically has several pooling processes running concurrently. One of its most recent projects has involved the assembly of a 25 hectare site in Roettgen on the edge of Bonn to build 300 homes along with local infrastructure. The ‘Am Hoelder’ site was formerly low-grade agricultural land, owned by 80 different landowners, including the council. After local consultation and negotiations with the landowners the council resolved to use land pooling to plan a new urban extension to accommodate much needed local housing. This involved the council assembling all land ownerships, then preparing a masterplan, obtaining outline planning permission and using local contractors to create serviced plots ready for housing development. Each landowner then received one or more of the 186 building plots according to their share of either the original land value or land area, minus public administration and infrastructure costs.

As the Council was also a landowner in the area it was able to deliver 52 council-owned plots for family housing and apartments, some of which it sold at reduced prices to younger families and first time buyers that live in the wider Bonn area. Others were sold directly to local builders for the construction of apartments according to council specifications.

expect local planning authorities to identify opportunities for villages to thrive, especially where this would support services and help meet the need to provide homes for local people who currently find it hard to live where they grew up;

make clear that on top of the allowance made for windfall sites, at least 10% of the sites allocated for residential development in local plans should be sites of half a hectare or less;

expect local planning authorities to work with developers to encourage the sub-division of large sites; and

encourage greater use of Local Development Orders and area-wide design codes so that small sites may be brought forward for development more quickly.

1.34 We are also supporting communities to take the lead in building their own homes in their areas. The new Community Housing Fund will support community-led housing projects such as community land trusts in many rural areas affected by a high number of second homes. Almost £20 million of the fund has been allocated to the South West, where this issue is particularly acute

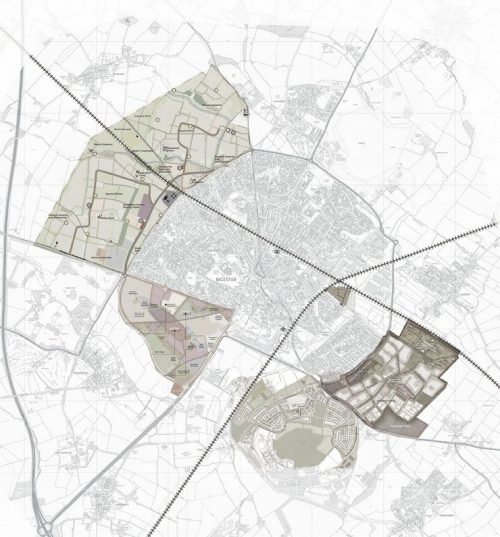

Case study: Bicester Garden Town

Photo credit: Bluesky World International Ltd/ Cherwell District Council

Over the next 15 years, Bicester will be transformed, with more than 13,000 new homes, 18,500 jobs, significant transport improvements and a regenerated town centre.

Bicester Garden Town is based on a clear vision, grounded in close community engagement. Extensive consultation has been undertaken to understand what people like about the town; what they hope to see improved; and how they picture Bicester in the future.

A comprehensive masterplan has been commissioned and home building is well under way:

At Graven Hill, the UK’s largest custom-build scheme for 2,000 homes on former Ministry of Defence land, the first 52 custom-build plots have been released for sale. People with a local connection have the opportunity to purchase first.

At North West Bicester, 6,000 homes are being built to the highest standards of sustainability. The first 87 new homes have been completed and new residents are moving in.

Bicester is also part of NHS England’s Healthy New Towns programme. This is exploring opportunities to use the built environment to promote healthy lives, alongside new models of health and care services, to improve the community’s physical health, mental wellbeing and independence.[30]

A new generation of new communities

1.35 We need to make the most of the potential for new settlements alongside developing existing areas. Well-planned, well-designed, new communities have an important part to play in meeting our long-term housing needs. Provided they are supported by the necessary infrastructure, they are often more popular with local communities than piecemeal expansion of existing settlements. Policy Exchange, for example, have highlighted the benefits of garden villages.[31]

1.36 The Government is already supporting a new wave of garden towns and villages, and will work with these and any future garden communities to ensure that development and infrastructure investment are as closely aligned as possible. We will also legislate to allow locally accountable New Town Development Corporations to be set up, enabling local areas to use them as the delivery vehicle if they wish to. The Government will also explore what opportunities garden cities, towns and villages might offer for bringing large-scale development forward in ways that streamline planning procedures and encourage locally-led, high quality environments to be created. The Centre for Policy Studies proposed the idea of ‘pink zones’ with this goal in mind and we are looking carefully at their recommendations.[32]

Green Belt land

1.37 Our Manifesto commits ours to be the first generation to leave the natural environment better than we found it – which we will take forward through our 25 Year Environment Plan. The Green Belt is highly valued by communities, particularly those on the edge of urban areas. The fundamental aim of Green Belt, since its introduction in the 1950s, has been to prevent urban sprawl by keeping land permanently open. It has been largely successful in this aim – the percentage of land covered by Green Belt has remained at around 13% since at least 1997.33 However parts of it are not the green fields we often picture, and public access can be limited, depending on ownership and rights of way.

1.38 In the last Parliament, the Government increased Green Belt protection by abolishing the unpopular and counter-productive Regional Strategies that sought to delete areas of Green Belt. Our manifesto reiterated our commitment to protecting the Green Belt. The National Planning Policy Framework is already clear that Green Belt boundaries should be amended only “in exceptional circumstances” when plans are being prepared or revised, but does not define what those circumstances are. The Government wants to retain a high bar to ensure the Green Belt remains protected, but we also wish to be transparent about what this means in practice so that local communities can hold their councils to account.

1.39 Therefore we propose to amend and add to national policy to make clear that:

authorities should amend Green Belt boundaries only when they can demonstrate that they have examined fully all other reasonable options for meeting their identified development requirements, including:

–– making effective use of suitable brownfield sites and the opportunities offered by estate regeneration;

–– the potential offered by land which is currently underused, including surplus public sector land where appropriate;

–– optimising the proposed density of development; and

–– exploring whether other authorities can help to meet some of the identified development requirement.

and where land is removed from the Green Belt, local policies should require the impact to be offset by compensatory improvements to the environmental quality or accessibility of remaining Green Belt land. We will also explore whether higher contributions can be collected from development as a consequence of land being released from the Green Belt.

1.40 We welcome other suggestions for what reasonable options local authorities should be expected to examine before amending Green Belt boundaries.

Strengthening neighbourhood planning and design

1.41 New development affects us all, whether by providing a place to live or as something that affects the look and feel of where we live. That’s why we want communities to have a more direct say over development in their area.[34] The neighbourhood planning movement has already been successful in encouraging communities to play a more active role in shaping their place, in terms of both how much and what gets built. Over 270 neighbourhood plans have come into force since 2012. Analysis suggests that giving people more control over development in their area is helping to boost housing numbers in plans. Those plans in force that plan for a housing number have on average planned for approximately 10% more homes than the number for that area set out by the relevant local planning authority.[35]

1.42 The Neighbourhood Planning Bill contains a number of measures to encourage the preparation of neighbourhood plans, by giving them full weight in the planning process as early as possible; introducing a streamlined procedure for modifying neighbourhood plans and areas; and requiring local planning authorities to set out how they will help neighbourhood planning groups and involve communities in their wider plan-making activity.

1.43 To further support the process:

the Government will make further funding available to neighbourhood planning groups from 2018-2020, so they can access the additional support they might need, for example where they allocate sites for housing and in planning for better design;

we propose to amend planning policy so that neighbourhood planning groups can obtain a housing requirement figure from their local planning authority, to help avoid delays in getting a neighbourhood plan in place.

1.44 We want to ensure that communities can influence the design of what gets built in their area.

Local people want new developments to reflect their views about how their communities should evolve, whether it is in keeping with the traditional character of their area or a beautiful contemporary design that adds to the existing built environment. Good design is also fundamental to creating healthy and attractive places where people genuinely want to live, and which can cater for all members of the community, young or old.

1.45 73 per cent of people say they would support the building of more homes if well designed and in keeping with their local area.[36] That’s why the National Planning Policy Framework is clear about the importance of good design, but too often local people hear about schemes late in the day, after a planning application has been submitted. Many places lack clear design guidance or codes that set early expectations for both developers and the community. Inadequate community involvement and insufficient certainty can fuel objections, cause delays and increase the risk of poor quality outcomes.

1.46 To improve the approach to design, the Government proposes to amend the National Planning Policy Framework to:

expect that local and neighbourhood plans (at the most appropriate level) and more detailed development plan documents (such as action area plans) should set out clear design expectations following consultation with local communities. This will provide greater certainty for applicants about the sort of design which is likely to be acceptable – using visual tools such as design codes that respond to local character and provide a clear basis for making decisions on development proposals;

strengthen the importance of early pre-application discussions between applicants, authorities and the local community about design and the types of homes to be provided;

make clear that design should not be used as a valid reason to object to development where it accords with clear design expectations set out in statutory plans;

recognise the value of using a widely accepted design standard, such as Building for Life,[37] in shaping and assessing basic design principles. These principles are crucial to the success of a scheme, but often get less attention than what a house looks like. They should be reflected in plans and be given sufficient weight in the planning process.

1.47 The Government intends to collaborate with planning authorities and the development industry to ensure that effective policies and processes for securing good design locally are identified and publicised. New funding to boost the capacity and capability of local authorities will also help communities develop policies and frameworks for securing better design in their areas.

1.48 To really feel involved in the process, we need to help local people to describe what good design and local character looks like in their view. The longer-term ambition is that the Government will support the development of digital platforms on design, to create pattern-books or 3D models that can be implemented through the planning process and used to consult local people on potential designs for their area.

Building good quality homes

1.49 An effective system of Building Regulations and building control is essential to ensuring that homes are built to good quality standards, are safe, highly energy efficient, sustainable, accessible and secure. The fundamentals of the Building Regulations system remain sound and important steps were taken in the last Parliament to rationalise housing standards.

Case study: The Avenue, Saffron Walden

Photo credit: © Tim Crocker

The Avenue in Saffron Walden, by housebuilder Hill, a medium-sized builder, is an example of delivering sensitive design that responds well to its context and optimises development on a suburban infill site.

A total of 76 new homes are inserted into a conservation area in a historic market town and a semi-rural landscape. The project takes its cue from the fabric and grain of Saffron Walden and the Essex countryside. The layout is made up of a tree lined avenue and series of intimate courtyards that preserve sensitive local landscape features and engenders a sense of community.

New detached houses for market sale, affordable family houses and smaller homes for the over-55 market are provided to address local housing need. The layout avoids the use of standard type plans and each home responds to its location, aspect and its relationship to its neighbours, creating individuality and variety. Building forms and the palette of materials draws from local traditional references without resorting to pastiche.

The development won a RIBA National Award in 2016.

The All Party Parliamentary Group for Excellence in the Built Environment has since looked into the quality and workmanship of new build housing in England[38]. The Government will keep requirements under review, to ensure that they remain fit for purpose and meet future needs. This includes looking at further opportunities for simplification and rationalisation while maintaining standards.

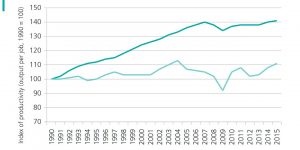

1.50 Since 1990, we have seen a significant improvement in the quality of Britain’s new build homes that has helped keep bills as low as possible and cut carbon emissions. But there is more to do, particularly if we want to avoid consumers having to carry out expensive, inconvenient retrofit at a later date. We have started work on a review of the cost effectiveness of current energy performance standards, which will have due regard to our domestic fuel poverty and climate change targets. We will consult on improving requirements on new homes this Parliament if evidence suggests that there are opportunities to do so without making homes less affordable for those who want to buy their own home.

More detail will be set out in the Government’s forthcoming Emissions Reduction Plan.

Using land more efficiently for development

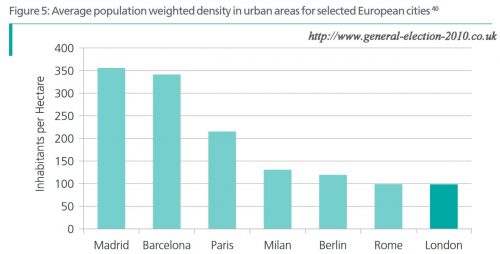

1.51 Not all development makes good use of land, especially in areas where demand is high and available land is limited. London, for example, is a relatively low-density city especially in its suburbs. When people picture high-density housing, they tend to think of unattractive tower blocks, but some of the most desirable places to live in the capital are in areas of higher density mansion blocks, mews houses and terraced streets.[39]

Figure 5: Average Population Weighted Density in Urban Areas for Selected European Cities [40]

1.52 A locally led approach is important to ensure that development reflects the character and opportunities presented by each area. At the same time, authorities and applicants need to be ambitious about what sites can offer, especially in areas where demand is high and land is scarce, and where there are opportunities to make effective use of brownfield land.

1.53 To help ensure that effective use is made of land, and building on its previous consultations,[41] the Government proposes to amend the National Planning Policy Framework to make it clear that plans and individual development proposals should:

make efficient use of land and avoid building homes at low densities where there is a shortage of land for meeting identified housing requirements;

address the particular scope for higher-density housing in urban locations that are well served by public transport (such as around many railway stations); that provide scope to replace or build over low-density uses (such as retail warehouses, lock-ups and car parks[42]); or where buildings can be extended upwards by using the ‘airspace’ above them;

ensure that the density and form of development reflect the character, accessibility and infrastructure capacity of an area, and the nature of local housing needs; and

take a flexible approach in adopting and applying policy and guidance that could inhibit these objectives in particular circumstances; for example, avoiding a rigid application of open space standards if there is adequate provision in the wider area.

1.54 The Government would welcome ideas on how planning policy can further encourage more innovative uses of land in areas of high housing need, including considering new permitted development rights. Consultation questions are set out in the annex.

1.55 The use of minimum space standards for new development is seen as an important tool in delivering quality family homes. However the Government is concerned that a one size fits all approach may not reflect the needs and aspirations of a wider range of households. For example, despite being highly desirable, many traditional mews houses could not be built under today’s standards. We also want to make sure the standards do not rule out new approaches to meeting demand, building on the high quality compact living model of developers such as Pocket Homes.[43] The Government will review the Nationally Described Space Standard to ensure greater local housing choice, while ensuring we avoid a race to the bottom in the size of homes on offer.

20 Monitoring by DCLG and the Planning Inspectorate

21 The National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) sets out the Government’s planning policies for England and how these are expected to be applied. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-planning-policy-framework–2

22 Local Plans Expert Group (2016) Local Plans: Report to the Communities Secretary and to the Minister of Housing and Planning. http://lpeg. org/; DCLG (2015) National Planning Policy: Consultation on proposed changes. Available at: www.gov.uk/government/consultations/national-planning-policy-consultation-on-proposed-changes; DCLG (2016) Technical consultation on implementation of planning changes. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/507019/160310_planning_consultation.pdf; DCLG (2016) Consultation on upward extensions in London. Available at: www.gov.uk/government/consultations/upward-extensions-in-london;DCLG (2016) Rural Planning Review: Call for Evidence. Available at: www.gov.uk/government/consultations/rural-planning-review-call-for-evidence.

23 Written Statement made by the Minister of State for Housing and Planning, 20 July 2015. Available at: https://www.parliament.uk/documents/ commons-vote-office/July%202015/21%20July/8-Communities-and-Local-Government-Local-Plans.pdf

24 Where these strategies require unanimous agreement of members of the combined authority concerned.

25 National Planning Policy: Consultation on proposed changes. Available at: www.gov.uk/government/consultations/national-planning-policy-consultation-on-proposed-changes.

26 DCLG (2016) Estate Regeneration National Strategy. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/estate-regeneration-national-strategy

27 DCLG (2015) National Planning Policy: Consultation on proposed changes. Available at: www.gov.uk/government/consultations/national-planning-policy-consultation-on-proposed-changes

28 Small sites for this purpose are those capable of accommodating fewer than 10 units, or which are smaller than 0.5ha.

29 In relation to ‘rural exception sites’ which are small sites used to provide affordable housing for local communities on land which would not normally be released for homes, as defined in the National Planning Policy Framework. Local Authorities can set a ‘local connection’ test to ensure the home goes to those local people who need them most.

30 Further information at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/ourwork/innovation/healthy-new-towns/

31 Policy Exchange, Garden Villages: Empowering localism to solve the housing crisis https://policyexchange.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/garden-villages.pdf

32 Boyfield K and Greenberg D (2014) Pink Planning. Available at: https://www.cps.org.uk/publications/pink-planning-diluting-the-red-tape/

33 DCLG Local authority green belt statistics for England: 2015 to 2016 https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/local-authority-green-belt-statistics-for-england-2015-to-2016

34 For example research by the Prince’s Foundation has highlighted how effective community involvement is essential for creating successful places and securing public support for new development: http://www.housing-communities.org/’

35 DCLG (2016) Neighbourhood Planning – progress on housing delivery. Available at: https://mycommunity.org.uk/2018/03/15/new-neighbourhood-planning-programme-changes-to-my-community-everything-you-need-to-know/

36 National Housing and Planning Advice Unit (2010) Public Attitudes to Housing. Available at: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov. uk/20110203064124/http://www.communities.gov.uk/documents/507390/nhpau/pdf/16127041.pdf

37 Birkbeck D and Kruczkowski S (2015) Building for Life 12: The sign of a good place to live. Available at: www.designcouncil.org.uk/resources/ guide/building-life-12-third-edition.

38 APPG for Excellence in the Built Environment (2016) More Homes, fewer complaints: report from the Commission of Inquiry into the quality and workmanship of new housing in England. Available at: http://cic.org.uk/services/reports.php

39 Create Streets have looked at the potential for high-density housing at Mount Pleasant, London: http://www.academia.edu/10797484/Mount_Pleasant_Circus Pleasant_Circus

40 Lavalle, Carlo; Aurambout, Jean-Philippe (2015) UI – Population weighted density (LUISA Platform REF2014). European Commission, Joint Research Centre (JRC). Available at: http://data.jrc.ec.europa.eu/dataset/jrc-luisa-ui-population-weighted-density-ref-2014

41 National Planning Policy: Consultation on proposed changes. Available at: www.gov.uk/government/consultations/national-planning-policy-consultation-on-proposed-changes; DCLG (2016); Consultation on upward extensions in London. Available at: www.gov.uk/government/ consultations/upward-extensions-in-london;DCLG (2016

42 JLL (2017) Driving Innovation Available at: https://www.jll.co.uk/en/newsroom

43 https://www.pocketliving.com

Previous : Introduction Our Housing Market is Broken